field notes from the tenth department

2013 - present

In 1864, Fyodor Dostoevsky published Notes from Underground. Heralded as the first existentialist novel, Notes confronts through an unnamed narrator, generally referred to as the Underground Man, the human experience and universal desire to ascribe meaning to one’s life.

Inspired by Dostoevsky, Ralph Ellison released Invisible Man in 1952. Ellison’s protagonist, also unnamed, confronts the meaning of his existence, but in a world that renders him socially invisible — a racialized other who is both hypervisible and erased by the white gaze.

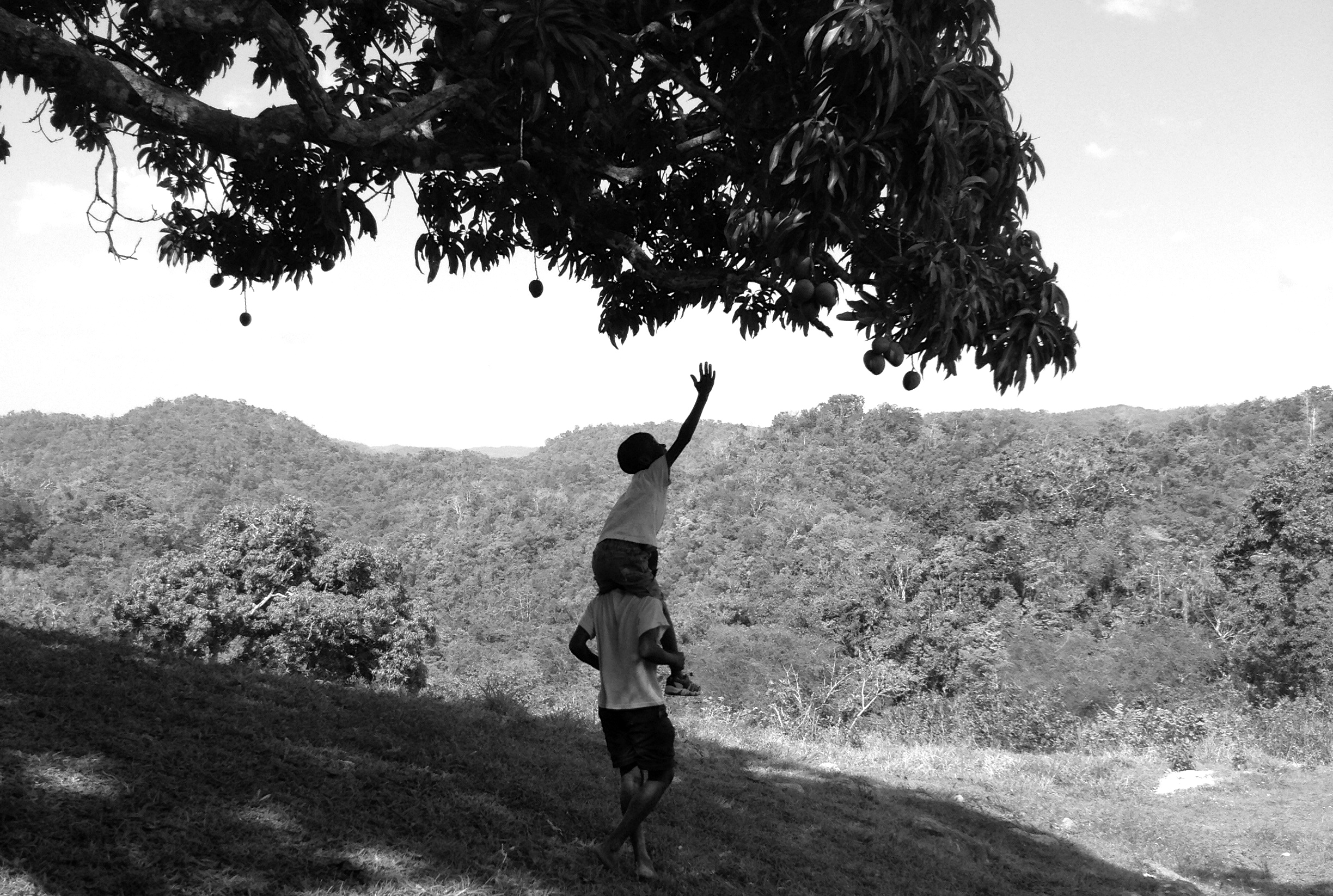

As a teenager, I read both Dostoevsky and Ellison and was moved by their invitations to bear witness through the lenses of unnamed protagonists. My takeaway from these texts was a sense that both characters embody the plight of “the every wo/man,” the faceless person who struggles to make sense of the chaos that surrounds her and to reconcile the Self that emerges. As a child born in the States to immigrant parents from Haiti, my Self-concept is caught between several realms. Tethered to memories of a "time before" and "across the water," Haiti is crucial to the ways in which I contemplate my positioning within the diaspora.

Haiti’s relationship to history and its impact has long suffered the silence of erasure. Approximately sixty years before the publication of Notes and a century before Invisible Man, in 1804 Haiti became the first non-European and Black republic to form from a successful slave rebellion and the second independent nation-state, after the United States, in the Western Hemisphere.

Although this was a Big Bang moment for the West, with ripples that would reach far across the waters of the Caribbean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean, the dream of Haiti has yet to be realized.

The post-revolutionary Haitian landscape underwent a process of departmentalization and the country was divided into nine geographical departments over two centuries by various national administrations. The subsequent tenth department, conceptualized by Haitian President Bertrand Aristide and his administration in the 1990s, became recognized as an extra-territorial unit of the republic, or more simply, the Diaspora. Haitians who occupy the tenth department remain tied to the island and cultivate their ties vis-à-vis a transnational identity. Even those who were born elsewhere and have never traveled to Haiti, engage in diasporic citizenship through their own long-distance nationalism.¹

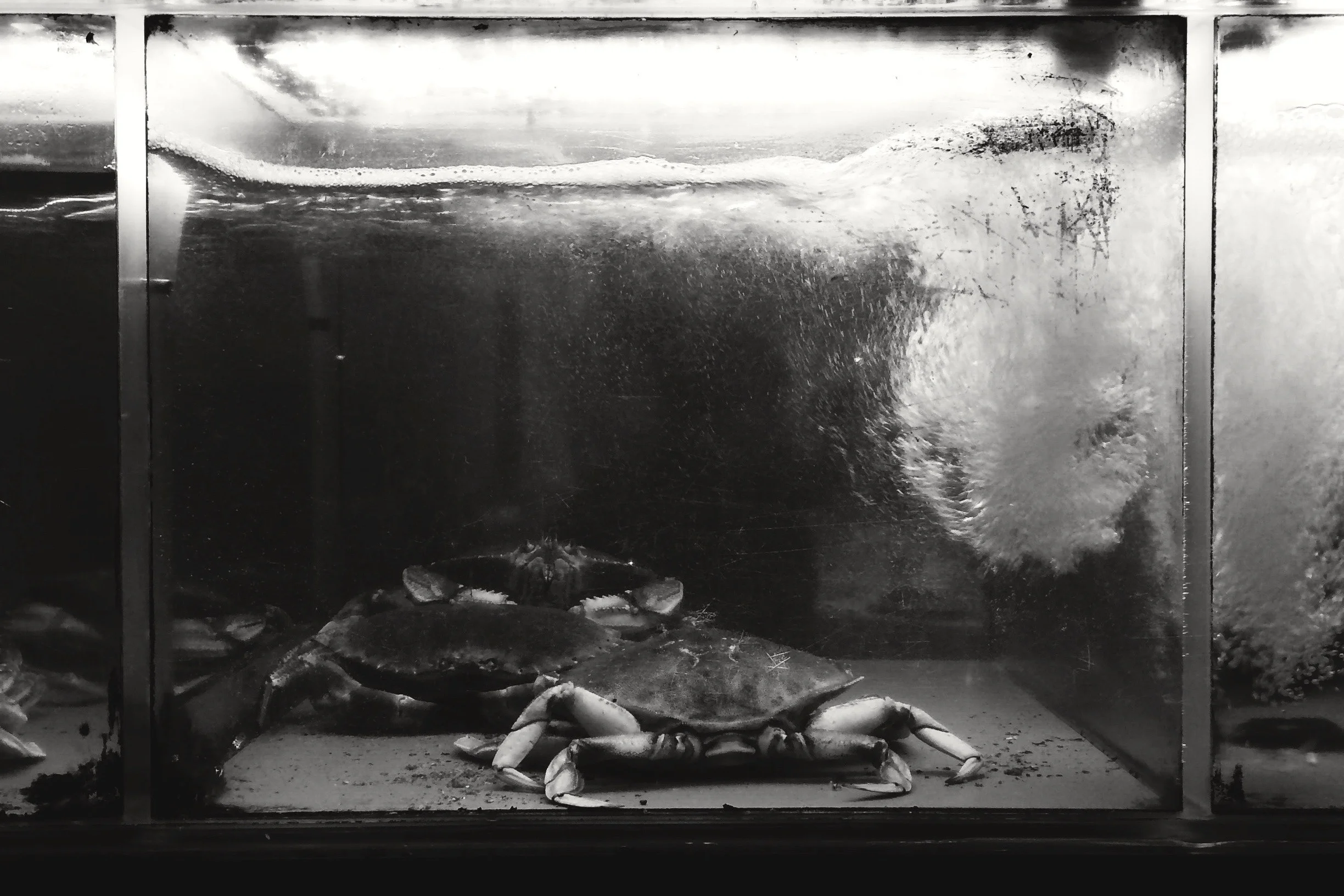

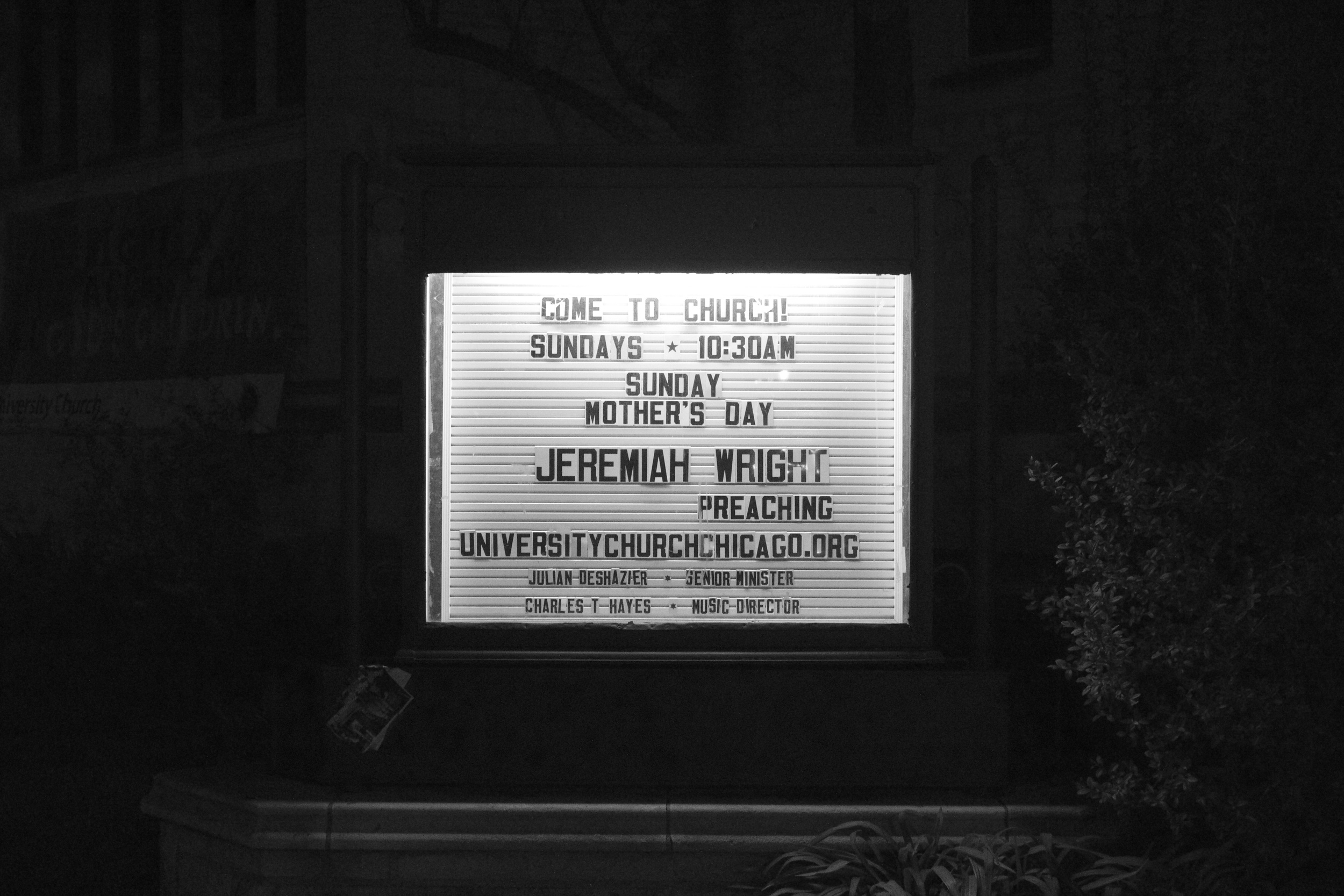

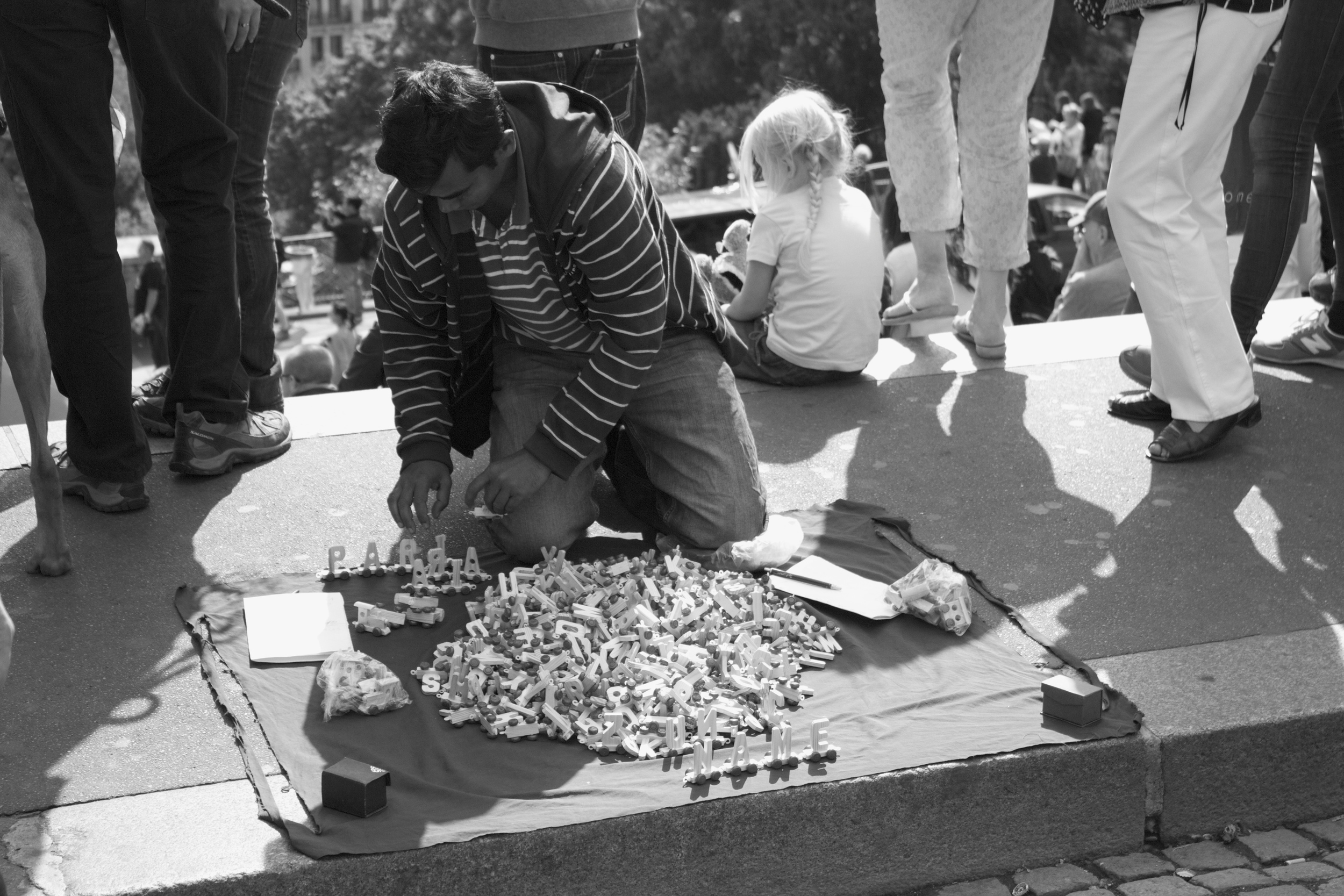

Inspired by the notion that diaspora exists as both a liminal and tangible site, I call this ongoing series of black and white photographs taken in transit, The Tenth Department.

The images are “field notes” — evidence of my presence in places where I’ve wrestled critically with how my body, Black, female, and Haitian (American) is marked by a racialized, gendered, and cultural invisibility.

'¹Michel S. Laguerre, Diasporic Citizenship: Haitian Americans in Transnational America (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1998), 162